- Biography

- Serenade for Strings in E

- Stabat Mater

- Slavonic Dances

- New World Symphony

- Symphony No. 7

- Piano Quintet in A

- Dumky Piano Trio

- Cello Concerto in B Minor

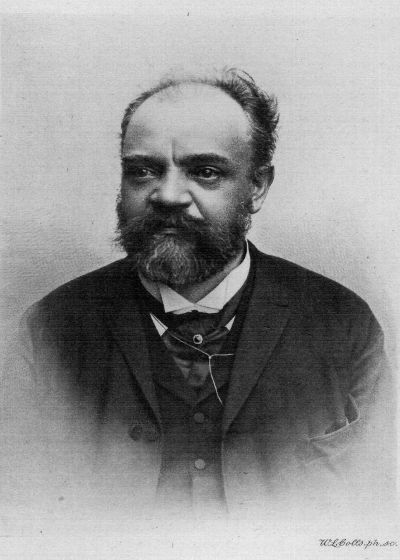

Biography

Dvorák is the foremost Czech composer.

Dvorák is the foremost Czech composer.

His music ranks alongside that of all the great writers of the nineteenth century, being performed by orchestras in concert halls all over the world.

He was definitely a composer’s composer: Tchaikovsky was a friend and admirer and Brahms was once moved to write, ‘I should be glad if something occurred to me as a main idea that occurs to Dvorak only by the way!’.

Dvorák had a very special talent for writing beautiful tunes, and his works are therefore littered with great melodies that sound so spontaneous you can’t help but have them ringing in your ears long after the music has stopped.

He started music at a very early age and, like all the other great composers, showed enormous promise straight away.

He found jobs as a viola player in various orchestras, notably the Czech National Opera Orchestra, and was often conducted by Smetana, one of his heroes.

It was here that he got his own first inspirations to write opera, and working alongside Smetana was undoubtedly of great benefit.

He was also obsessed with the works of Wagner and, having made contact with the maestro, is reputed to have attended every single performance of Wagner’s work at the German Theatre in Prague.

His own forays into the world of composing were not received with the wildest enthusiasm, but this did not deter him and he continued to write symphonies, string quartets and song cycles until, in the mid-1870s, no one could ignore him any longer.

Brahms had long championed his works and helped Dvorák’s career by getting him a publishing deal.

Dvorák had already won the Austrian State Prize four years running and finally made his mark with works such as the Serenade for Strings and the now immensely popular Slavonic Dances.

It was from then on that Dvorák never looked back.

He was invited all over the world both as a conductor and a professor of music.

He spent three years in the United States, where he wrote his Symphony No. 9 (The New World), but spent the last few years of his life in his native land in the city of Prague as the Director of the Conservatory.

Serenade for Strings in E

Serenade for Strings in E Op. 22: Moderato

1875, Chamber Music

Full of catchy lines, the Serenade for Strings was originally written as a five-movement suite, yet it sounds more like a chain of endless melodies that are hard to forget.

Stabat Mater

Stabat Mater Op. 58: Stabat Mater dolorosa

1877, Choral

Dvorák is not so well known for his choral work, yet this solemn and religious text is well handled, with a good use of melody.

Slavonic Dances

Slavonic Dance in G Minor No. 8, Op. 46

1878, Orchestral

Originally written as a piano duet, this fast and rhythmic folk dance is even more red-blooded in its orchestral version.

New World Symphony

Symphony No. 9 (‘New World’) Op.95: Largo

1884, Symphonies, Orchestral

The Czechs – or Bohemians, as they used to be called – have been famous as musicians as long as European music has been made, and, from chronicles of the Middle Ages, we can see that they held positions such as pipers and fiddlers to the great dukes and kings of France and Germany.

In the eighteenth century, Bohemian composers settled in France, Italy, Austria and Germany, making tremendous contributions to the new symphonic style, so therefore it is not surprising that Dvorák, whether he knew it or not, was following in a great Czech tradition when he accepted a job to come and teach at the National Conservatory of Music in New York – his arrival serving as an inspiration for his ‘New World’ Symphony.

As a good Romantic, Dvorák was firmly of the belief that great music must grow from the healthy soil of native folk music and, whilst in America, he identified the music of the Negroes and the American Indians as the sources for his composition, coupled with the inevitable Czech influences he carried within himself.

A slow introduction from the horns opens the otherwise well-paced first movement (Adagio; Allegro molto), which incorporates a lovely flute line that is reminiscent of ‘Swing Low Sweet Chariot’, one of Dvorák’s favourite spirituals.

It is the second movement (Largo), however, that contains the famous horn phrase played as a solemn procession.

The Scherzo that follows is bright and alive and could be a festive village scene full of dancing Indians or Czech peasants. The finale is a tremendous sweeping Allegro that recaps the previous three movements.

Symphony No. 7

Symphony No. 7 Op. 70

1885, Symphonies, Orchestral

Dvorák’s Symphony No. 7 was one of the most important he ever wrote – at least, according to him – for in June 1884 he had been made an honorary member of the London Philharmonic Society, and furthermore he had recently been completely overwhelmed by Brahms’s Third Symphony and wished to produce something of equal stature. The LPS invited him to write a work for them and he duly obliged, producing a symphony that is possibly eclipsed only by his ‘New World’ Symphony (No. 9).

Piano Quintet in A

Piano Quintet in A Op. 81

1887, Keyboard Works

This is a work that seems to be smiling at the listener. Set in four movements, a bright piano is contrasted with some strenuous string lines, as if the two parties are having a friendly conversation.

Dumky Piano Trio

Dumky Piano Trio Op. 90

1891, Chamber Music

A ‘dumka’ is a traditional Czech folk dance with alternating slow and fast sections, often based on the same theme. Dvorák uses this structure in combination with the more serious sonata form to produce a work of considerable charm.

Cello Concerto in B Minor

Cello Concerto in B Minor Op. 104: 3rd Movement

1894, Concerti, Orchestral

Dvorák’s cello concerto was the last thing he wrote while working in America: he began it in New York in November 1894 and finished it three months later. It was a stunning piece, and when Brahms first read the music he exclaimed:

‘Why on earth didn’t I know that it was possible to write a cello concerto like this? If I had only known, I would have written one long ago!’

When he took it back to his native Prague in 1895 Dvorák learnt of the death of his sister-in-law, Josephina Kaunic, and was deeply shocked. Not only had she been a friend, but when he was younger he had secretly fallen in love with her, writing a discreet love song for her entitled ‘The Cypresses’. There was, however, another of his songs which was her favourite, ‘Leave Me Alone’, the theme from which Dvorák incorporated into the coda of the cello concerto as a last reference to Josephina.

The first movement (Allegro) opens with a fiery orchestra sweep and the principal theme as a phrase from the clarinets. The solo cello then makes its entrance against a background of whispering violins and violas. The second, slow movement (Adagio ma non troppo) is full of emotional warmth, and the cello sings the melody of Josephina’s favourite song. The finale is a rousing dance-like movement which, according to Dvorák’s biographer, is filled ‘with the tone of happy anticipation of the composer’s early return to his own country.’ There is a melodious middle section, and finally the cellist joins the first violins in a duet of passionate tenderness. A brilliant climax for full orchestra rounds off one of Dvorák’s finest works.